This was originally written as a paper for an art history class in curation.

This was originally written as a paper for an art history class in curation.

Last year, my birthday fell shortly before David Bowie Is, the “first retrospective of the extraordinary career of David Bowie,” closed its run at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago. My wife surprised me with tickets to the long-sold-out show. We packed for a crash road trip, hopped into the car, and drove from Minneapolis to Chicago, listening our way with mounting excitement through the entire Bowie oeuvre during the 10-hour trip.

Viewing the exhibit was an overwhelming rush; the line to enter the museum had stretched around the block. The show was designed to hit attendees through multiple senses – as one walked through the space looking at objects, a location-sensitive headset would blast music or interview clips related to the object under view. The crowd itself – packed into the galleries as tightly as the fire marshals would allow – provided a constant buzz of energy as several rooms full of Bowie superfans communed with artifacts connected with the great man.

We left the exhibit exhausted and happily dazed. But on the drive back to Minneapolis, questions started to bubble up as we talked it over. What had we learned in that exhibit? It didn’t really seem like we’d gotten much in the way of new information. The experience had been intense and fun, but had there been an intellectual point? Had the whole thing really been an enjoyable but ultimately empty wallow in pop idolatry? As months passed and the undigested bolus of David Bowie Is lingered in my head, a slow, slinking surety settled in that it had all been a lot of sound and fury, signifying nothing.

The Exhibit Itself

David Bowie Is was originally curated by Victoria Broackes and Geoffrey Marsh, curators of theatre and performance at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. Publicity text for the exhibition states that “more than 400 objects, most from the David Bowie Archive—including handwritten lyrics, original costumes, photography, set designs, album artwork, and rare performance material from the past five decades—are brought together for the first time.” The exhibit traveled after its run at the V&A; its only stop in the United States was at the Museum of Contemporary Art (MCA) in Chicago, from September 23, 2014, to January 4, 2015, where local curatorial assistance was provided by Michael Darling.

As mounted at MCA, David Bowie Is stretched through eight galleries. In keeping with the exhibition’s retrospective nature, the artifacts on display were ordered chronologically through Bowie’s life, with individual galleries roughly conforming to career stages – there was the Formative Years and Struggling Young Artist Room, the Ziggy Stardust Room, the Post-Ziggy Cocaine Freakout Era Room, the Eighties and Beyond Room, the Eighties and Beyond Costume Annex, the Bowie Tries Acting Room, the Album Covers Nook, and a final Performance and Costume Extravaganza Gallery to sum things up (all hyperbolic titles mine, of course). To differentiate the galleries and eras, each room’s walls were painted a different color, ranging from pale blue to dark grays to an unusually vibrant red for a gallery setting; a couple of galleries were also lit in dramatic fashion to recreate the feel of a rock show. Each gallery included an introductory label with a title and a few paragraphs of text to establish the focus of that particular room.

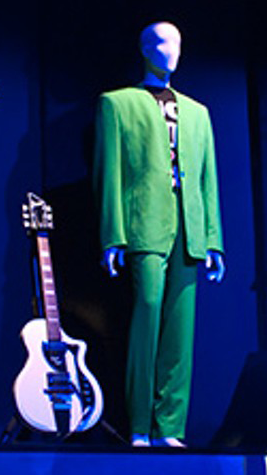

Lacking concrete numbers of how the objects on display fall within the stated categories of lyrics, costumes, photography, set design, album artwork, and performance material, I can’t say with certainty that the objects were dominated by costumes, but that’s certainly how it felt in the galleries. David Bowie Is overwhelmingly felt like a textiles show with some supporting materials. A number of Bowie (or Bowie-related) outfits were mounted on mannequins throughout the galleries: a vinyl Ziggy Stardust costume designed by Kansai Yamamoto, resembling the “wingsuits” worn by base-jumping daredevils. A lime green suit, the height of minimalist 1980s fashion. A psychedelic quilted jumpsuit posed in front of angled mirrors and a videoscreen. A mesh bodysuit with a pair of applique monster hands embracing the wearer from behind.

Perhaps the costumes dominated visually simply because of size – an outfit hung onto a mannequin takes up a human-sized amount of space (particularly when the mannequin is posed dramatically), while such other supporting objects as handwritten lyric sheets and small spoons used to portion out cocaine (displayed in the Post-Ziggy Cocaine Freakout Era Room, of course) could be packed several items to a vitrine. Certainly the staging of the exhibition favored the costumes. A general pattern repeated: a costumed mannequin (or a pair of them) on a wide, low platform, lit dramatically (usually from below, but sometimes from above), with a nearby label listing the designer and the tour/era in which Bowie wore it. Around the costume, on the platform, a larger supporting item or two – say, a saxophone still bearing traces of Bowie’s lipstick on the reed, again with a small label on the floor mentioning that the sax had been played on Diamond Dogs. On the wall surrounding the platform, framed photos with labels. Off to one side, vitrines holding smaller items in the lyric-sheets-and-cocaine-spoon class (usually with individual labels, occasionally with one label to a vitrine). In a few cases, a screen mounted on the wall behind the costumes, running looped video of the costume or props in use in a live performance, with the proximity-sensing headphones providing the appropriate soundtrack.

This arrangement served as the basic building block of David Bowie Is, with minor variations. I found it ironic that an exhibition purporting to celebrate the outré showmanship of a visionary artist (and this is the sort of language that exhibit materials leaned on heavily) was mounted in such a mundane fashion, with only some dynamic mannequin poses providing any real visual energy; setting aside the visual flair of the costumes themselves and some dramatic lighting in a couple of rooms, the nuts and bolts of the way the objects were displayed were not significantly different from what one would see at a well-funded county historical society’s exhibition of uniforms and personal effects of locals who served in World War II. On the other hand, I couldn’t think of any more innovative way to display what was, in the final analysis, a collection of costumes and papers leavened with a few musical instruments and photographs. It may be the case that innovation in exhibition design runs aground on the hard realities of practicality.

One genuinely innovative element of David Bowie Is was the aforementioned location-aware audioguide headsets, provided (as visitors were frequently reminded) by exhibition cosponsor Sennheiser. An object-based exhibition about a musician suffers from a serious dancing-about-architecture problem; barring the occasional cutting-edge costume enthusiast, music is the central reason a person would go to an exhibition about David Bowie, but incorporating music into a large exhibition is a tricky matter. Speakers playing directly into the galleries would quickly run into practical limits on how many concurrent audio clips could play in close proximity to each other without creating a maddening sonic jumble, not to mention serious concerns about appropriate volume levels for different visitors.

The location-aware audioguide headsets were an elegant solution to this problem; I found it very effective, for example, to see a mannequin wearing a quilted Ziggy Stardust jumpsuit standing in front of a video screen showing Bowie wearing the outfit, walk towards it, and abruptly start hearing the synched live audio performance of Bowie singing “Starman” as I approached. Or in several cases, the vitrines full of notebook sheets and personal ephemera were enlivened by related interview clips that played as one got near.

There were downsides to the headphone setup. For one thing, the aforementioned interview clips, while often illuminating the objects on display in vitrines, also competed for one’s attention while looking at the items; it is not easy to simultaneously read a handwritten diary and keep track of an audio interview. Also, in a packed gallery, movement was not always fluid, sometimes leaving one trapped in a location waiting for a bottleneck to clear, condemned to hear a repetitive loop of that spot’s audio content until the dam broke. And one never knew for sure that you’d made it all the way through an audio clip until you heard it start to repeat itself.

More than that, though, the headphones were isolating. As mentioned, I attended David Bowie Is with my wife. We go to museums together quite often, and often talk (in quiet, respectful tones) about things on display or interesting text on labels; this interaction is a core part of our usual museum experience, as I believe it is for many people. In this case, the headphones intervened. It was not really possible to talk about anything on display without first – at bare minimum – going through an elaborate pantomime to indicate “hey, take your headphones off, I have something to say.” In practice, our interactions were limited to dramatic eye and hand gestures on the order of “hey, get a load of this!”

The isolating phenomenon is even stranger when one remembers that the galleries were packed with people, each of them isolated in their own headphone silo. David Bowie Is was without question the largest “alone together” situation I have ever experienced. Not everyone saw this as a negative, though; while working on this paper, I reached out to a friend on Twitter who’d seen and loved the exhibit, and discovered that he found the headphone-induced isolation as a good thing:

I liked the most that the way it was presented with the headphones that despite being crowded you felt you were alone there. Especially since it wasn’t a guided audio tour you could bounce to what you wanted to see/what wasn’t mobbed at the moment. Also since everyone was listening to their own headphones it was silent. I was completely absorbed into the exhibit in a way I usually am not. It’s tough to explain. It isolated me from the other people, but submerged me into the actual exhibit. It probably helped that I was there alone, so there was no social component to my experience.

This was an element I had not considered, but I think his point his very good; if I had gone to David Bowie Is by myself, I probably would have found the headphone isolation a bit liberating, too.

So What Was All That About?

As mentioned previously, the MCA’s marketing materials for David Bowie Is describe the exhibit as the

first retrospective of the extraordinary career of David Bowie—one of the most pioneering and influential performers of our time. More than 400 objects, most from the David Bowie Archive—including handwritten lyrics, original costumes, photography, set designs, album artwork, and rare performance material from the past five decades—are brought together for the first time.

This works as marketing copy, but provides little in the way of revealing curatorial intent. V&A curators Victoria Broackes and Geoffrey Marsh say a bit more in their introduction to the exhibit’s catalogue:

Hundreds of thousands of words in many languages have been written about Bowie, from the carefully considered to the intuitive response, and even bitter festering rage. … No previous book, however, has illuminated and drawn in full on The David Bowie Archive. That exceptional collection, astutely amassed over many years and spanning the entirety of Bowie’s career, has set the course for this book and the Victoria and Albert Museum exhibition. Both seek to link Bowie’s art and music, through artefacts from costume to film, into the wider cultural narrative represented by the Museum’s own collections. Bowie’s music catalogue together with his archive gives us wonderful material for a gallery exhibition, but only partly explain his iconic role and growing status. The remaining parts of the picture lie in the changes in the world around us and with us, his audience.

Linking Bowie’s work to a wider cultural narrative is a reasonable goal for an exhibition, although a vague one. But the rest of that sentence is actually rather alarming for someone viewing the exhibition anywhere other than the V&A: if the “Museum’s own collections” are an important component in the linkage Broackes and Marsh hope to create, they were a component completely absent from the Chicago instance of the show. The wider supporting context of the V&A just isn’t there to provide linkage or even reference, and the Chicago version of the show made no effort to create substitute linkages through MCA’s collections.

Lacking this external object-based linkage, the primary tool available to Broackes and Marsh to connect the objects on display to the wider cultural narrative is the gallery label. But one can provide only so much context in 50 words; the introductory labels in each gallery provided a bit more context, but the shortcomings of traditional narrative gallery labels are an established fact in modern museum discourse. They are useful, but they can only get you so far. The labels in David Bowie Is tended strongly towards providing utilitarian information about where the object came from and where and when Bowie used it.

In terms of what was actually on display in the galleries, then, Broackes and Marsh came up short in their goal to connect Bowie’s career to the wider cultural narrative; there simply wasn’t much on the platforms and vitrines – or on the labels mounted around them – to tell the visitor much about David Bowie’s relation to the wider culture that he or she wouldn’t have already known walking into the galleries (and remember that, since MCA was the only US stop for the show, the exhibition’s audience had to be willing to at minimum spend $25 for a ticket, brave crowds, and in many cases travel hundreds of miles to see the show; these barriers to entry inevitably skewed the audience to self-selected Bowie enthusiasts).

The repeated mentions in both the marketing materials and catalog text of the show’s reliance on the David Bowie Archive are telling. For one thing, it provides a crucial insight into Broackes’ and Marsh’s parameters when putting the show together. Presumably they scoured the archive for the materials that they felt did the best job of presenting Bowie’s story, which is reasonable, but it does mean that they were constrained by what was available to them in the archive. As curatorial constraints go, that’s not a terrible one, although it does allow the reductive view that the show is just a professional staging of the more interesting portions of a famous person’s stuff.

But that’s needlessly harsh and misses the bigger picture. I’ve leaned negative when analyzing the staging of the exhibit, but if I go to the subjective, I can’t deny the intensity of my enjoyment when I was in the galleries themselves, and for weeks afterwards until I started thinking about the nuts and bolts of the show. I know I’m not alone in greatly enjoying the experience of David Bowie Is. I distinctly remember my fellow viewers looking happy and even transported as we were all alone together in the galleries. I remember the excited party atmosphere in the lines waiting to get in. And I’ve noticed that I can’t mention the exhibit on Twitter without people popping up to mention how much they loved it (which is how I wound up with the above countering opinion on the headsets).

So clearly David Bowie Is worked on some level. And that level is actually buried towards the bottom of Broackes’ and Marsh’s curatorial statement. Remember that last line: “the remaining parts of the picture lie in the changes in the world around us and with us, his audience.” That is the key to David Bowie Is. As a traditional interpretive exhibit, the show was so-so. But as a Hans Ulrich Obrist-ian facilitation of a space where enthusiasts could gather to essentially revel in their enthusiasm, the show is a smashing success. Put another way, Broackes and Marsh used the Bowie archive to assemble a situation in which the audience (largely self-selected, as I mentioned previously) brought the missing piece of the exhibit in with them.

What Do We Take From This?

I take two major lessons from analyzing David Bowie Is: one practical, one more philosophical. On the practical side, the exhibit really drove home for me how powerful textiles can be. I was at first nonplussed by the decision to build the displays around costumes, but after considering it, I think this was a great choice. This was a show about a person, and the series of mannequins dressed in that person’s (very idiosyncratic) clothes served to humanize the entire endeavor; one could look at the mannequin as a character moving through a narrative, with changing clothes indicating changing circumstances. If the exhibit was concerned with identity, foregrounding costumes was an excellent way to do this. Fashion is a key vehicle through which people project their identities into the world; “the clothes make the man” is a popular saying for a reason. So the show’s focus on costumes was a good choice both visually/aesthetically and theoretically.

The more philosophical lesson is that an exhibit can succeed by transcending its own limitations. I don’t feel that the interpretive materials in the gallery did much to further the exhibition’s stated goal of linking David Bowie to a broader cultural context. But I still enjoyed the show and think back on it fondly. If David Bowie Is succeeded, it was as a facilitated space in which people could semi-communally surf in their own enthusiasm. I’m not entirely convinced that this is a manner in which Broackes and Marsh intended the show to work, but it certainly did, and their mention of the remaining parts of the picture lying with the audience lends credence to the idea that they were aware of this dimension. Certainly, it’s hard to argue that a retrospective show about a celebrity wouldn’t ultimately rest on some level of audience enthusiasm about the subject.

There is probably a larger argument to be made about the ins and outs of that approach to museum programming. For one thing, a show whose success relies on enthusiasm brought into the galleries by participants can only work for a limited number of people; I can’t imagine that David Bowie Is offered much to someone who wasn’t already interested in the man. The self-selecting nature of the audience mitigated this problem in this case, but this seems like dangerous ground for a museum to tread. It’s easy to imagine a dystopian future where every museum show is just the celebration of a celebrity, soaking up an unhealthy amount of cultural bandwidth (coming soon to the Walker Art Center: Adam Sandler Rulez). I don’t think that there are all that many public figures who are interesting and multifaceted enough to make a best-picks-from-a-rich-person’s-stuff show about them transcendent. But I think David Bowie is.