or Postmodernism is Closer Than You Think

So, right now social media is aflame with talk of Jordan Peterson, the latest half-bright pile of mud to figure out that there’s money to be made telling angry young men that they’re right and special. Peterson and the controversy surrounding him are too dull to get into here, but I bring him up because part of his program includes bemoaning postmodernism and accusing it of destroying our morals, corroding society, corrupting the youth of Athens, yada yada yada.

I yada there because this isn’t a new thing. Howling incoherently about postmodernism has turned into a byword of the American right, especially its angrier, weirder wings (for instance, the vague acquaintance from high school, now blocked, who swooped into a facebook thread about the US withdrawal from the paris climate accords and told all of the participants that we were postmodernism-poisoned liberals and cultural Marxists who should kill ourselves). And I say “incoherently” advisedly; I just finished a master’s in art history, wherein I spent a lot of time talking and reading about postmodernism, and I can assure you that very little of it had to do with a vast liberal conspiracy to undermine the work of brave patriots like Alex Jones.

So what’s postmodernism? That’s a complicated thing to lay out, actually, for several reasons. For one thing, postmodernism manifests itself differently in different cultural spheres; architectural postmodernism isn’t exactly the same thing as literary postmodernism, and both are slightly different from postmodernism in visual art, and so on. This is a thing—THE thing—about culture, that answers are usually more complicated and boundaries more fuzzy than we’d like. But that’s the way it is. Anyway, in all of these spheres, postmodernism is (as the name would imply) a cultural reaction to modernism, which in turn was a reaction to (or at least existed in the context of) the romanticism of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Again, I’m simplifying the hell out of things here, but hopefully in a useful way. Speaking really broadly, modernism was a push towards a theoretical rational order, often marked by form-follows-function minimalism. Think the paintings of Piet Mondrian, or the geometric glass buildings of Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, or the sparse, structured prose of Ernest Hemingway. The uniting theme here is a desire to pare things down to their essence, and (generally) to make the world make sense in terms of rational, quantifiable systems.

Postmodernism (once again, speaking really broadly) rose from the recognition that the world couldn’t really be contained, described, and modeled in the tight, orderly boxes demanded by modernism. And it can’t, for reasons too complicated to get into here, but 20th century developments in math, physics, and culture all ran into some kind of uncertainty or incompleteness on the outer fringes. (Thus, the squishiness of defining postmodernism is both ironic and kind of the point.) Where modernism implies (if often between the lines) a crystalline objective order to everything, postmodernism recognizes the semiotic implication that just about everything in human culture exists in relation to something else (this, I guess, is what drives the political right nuts, if they see it as a push back against tightly-strictured, clear, rational morality handed down by god; I submit that postmodernism isn’t really the problem in that model). Think of it this way: how do you define a word, any word? You do it through other words. Which in turn are defined by other words. It’s a giantic, neverending web of connections that sort of resembles the surface of a waterbed rather than a crystalline bedrock. Which sounds bad and confusing, but the good news is that by this part you’ve read more than 500 words-dependent-on-other-words about the subject and hopefully picked up some kind of informational content; in other words, it turns out that human culture gets along just fine without fixed points.

Anyway: a few hallmarks of postmodernism emerge from what I just said. One is a (usually) playful sense; you can think of postmodernism as a trickster Bugs Bunny character constantly tweaking modernism’s rules-bound Daffy Duck. Another, reflecting the whole interconnected-web-of-referentiality thing, is a propensity towards reference (see the previous sentence for an example; by the way, ever notice that Bugs Bunny is essentially an animated Groucho Marx, even repeating some gags?). Finally, especially in literature, architecture, and film/TV, postmodernism shows an obsession with form and playful tweakings of it.

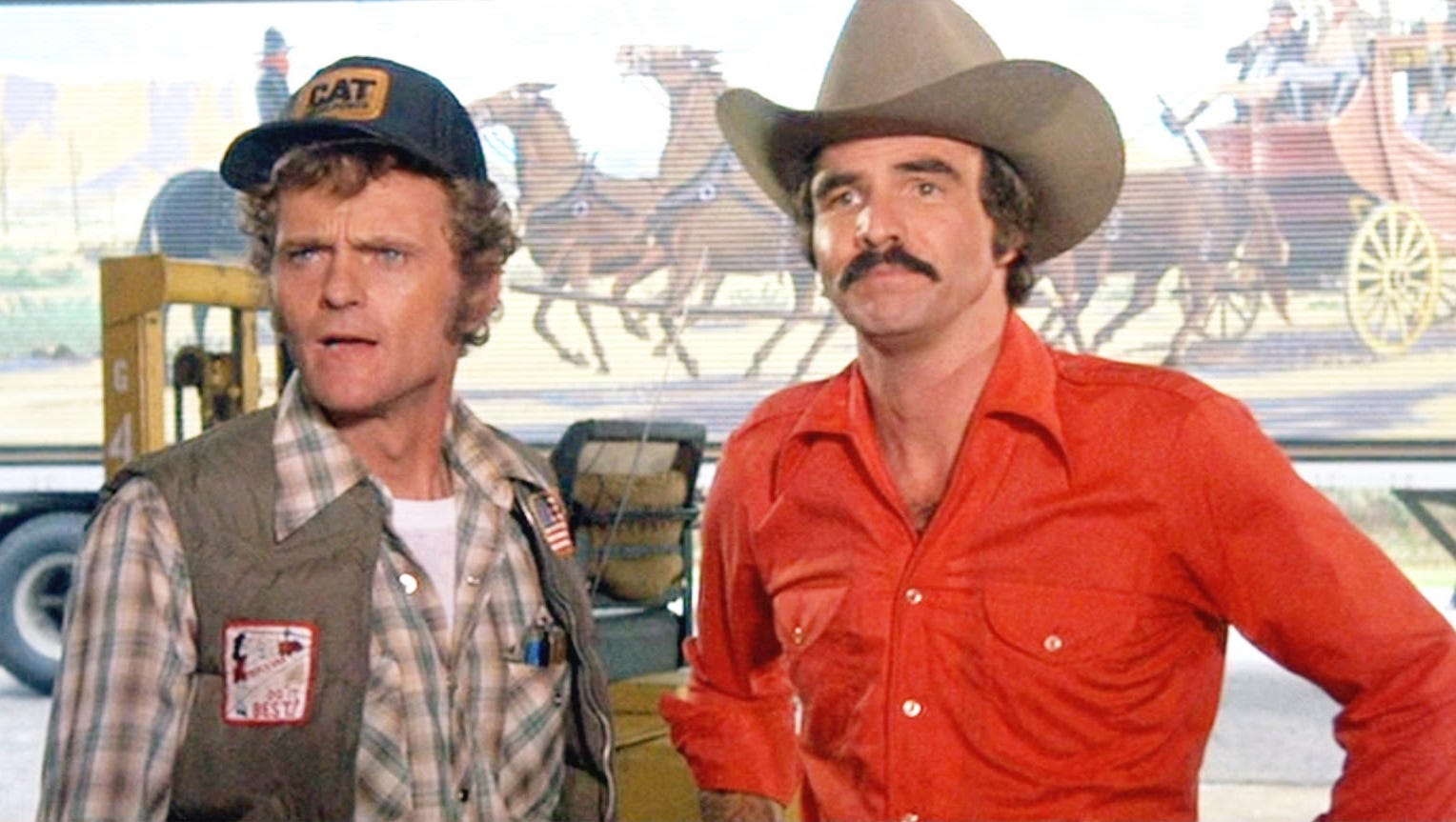

Which brings me back around to the American right. I’ve noticed a persistent love among people on the right for the movie Blazing Saddles. Jason Lewis, now a tea party republican congressman from Minnesota, often played the theme from Blazing Saddles during his time as a right-wing radio shouter in the Twin Cities. Conservative moaners about political correctness love to hold up Blazing Saddles as a movie that couldn’t be made today because the mean liberal scolds would kill it for being too un-P.C. The overlap between these people and people who decry postmodernism is for all intents and purposes total.

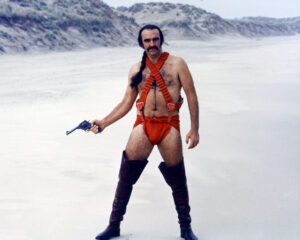

Which is dumb, because Blazing Saddles is a profoundly postmodern movie. It openly takes the constituent chunks of old-fashioned westerns and playfully remixes them, critiquing them in the process. This is the essence of postmodernism. It’s highly referential- some of the jokes don’t make sense unless you know about lawsuits Hedy Lamar filed. It deconstructs itself- look at the last act of the movie, where the action spills off of the set where the movie’s being filmed and takes over an entire movie studio. It’s hard to find a more postmodern moment than Slim Pickens, maybe-and-maybe-not breaking character, yells “Piss on you, I’m working for Mel Brooks!” before beating up Dom DeLuise. Honestly, if someone ever asks you what postmodernism is, you can give them a pretty good answer by just telling them to watch Blazing Saddles and think a little bit about what they’re seeing.

I’m not saying that Mel Brooks and his crew sat down and said “we’re going to make a movie that’s a massive exercise in postmodernism, and also includes fart jokes.” I’m sure they didn’t; that’s just not the way things work. Labels like these are almost always worked out after the fact, except for weird vanguardy cases where someone’s writing a manifesto. It’s more accurate that the cultural moment constantly moves forward and seeps into everything that’s created, and some time after the fact someone looks at it and says “yeah, that’s postmodernism” or “hey look, all of that stuff is similarly ornate, let’s call it baroque” or “boy, sure seems like some kind of rebirth, a renaissance if you will, happened in Europe there.” Postmodernism started popping up in at least the 40s and eventually came to be the dominant cultural mode of the west in the back half of the 20th century, continuing into today.

Which is to say that people moaning that postmodernism has made immoral soyboys out of all of us don’t know what they’re talking about. They are, ultimately, fish unknowingly complaining about the water they’re swimming in. And if, after complaining, they tune into any cultural product more sophisticated than Little House on the Prairie, they’re being pretty hypocritical.

(Postscript: since I brought it up and then just left it there, and someone’s bound to ask: the “it couldn’t be made today because it’s so un-PC” belief about Blazing Saddles has nothing at all to do with Saddles’ status as a profoundly postmodern movie. It’s a profoundly postmodern movie that happens to be about American race relations; Infinite Jest is a profoundly postmodern novel that has nothing much to say about race relations. Just because a work is one thing doesn’t mean anything about the other thing. Anyway, I don’t know that I buy that statement to begin with. The original possibility Blazing Saddles had a lot to do with Mel Brooks’ clout and production capabilities at that moment; the movie was pushing boundaries then, too, just as it would be now (even if the boundaries in question are different). Anyway, several movies come out every year that are more intentionally offensive than Blazing Saddles (and generally not as good). People who live in a world where multiple Human Centipede sequels have been filmed don’t have very strong legs to stand on when they talk about stuffy atmospheres stopping movies from being made.)

(Post-Postscript: another good moment of unacknowledged 1970s postmodernism was pointed out by pal Max Sparber, who observed how weird/great it is in the theme from Shaft that the backup singers get angry at the lead singer and then reconcile in admiration for the subject of the song, all within the text of the song itself.)

I lived with my grandparents during my senior year of high school. Surprisingly, given what was coming, this didn’t have anything to do with a big rupture with my parents or anything like that; my father had gotten a job in a tiny town in northwest Missouri, and I was convinced that graduating towards the top of a class of 8 people wouldn’t look as appealing to colleges as doing pretty well in a class of 230. So I suggested to my parents that maybe it made sense for me to stay in Blair, and they agreed. Legal guardianship was set up and, the day after I finished my junior year, I moved into what had been my grandmother’s bedroom.

I lived with my grandparents during my senior year of high school. Surprisingly, given what was coming, this didn’t have anything to do with a big rupture with my parents or anything like that; my father had gotten a job in a tiny town in northwest Missouri, and I was convinced that graduating towards the top of a class of 8 people wouldn’t look as appealing to colleges as doing pretty well in a class of 230. So I suggested to my parents that maybe it made sense for me to stay in Blair, and they agreed. Legal guardianship was set up and, the day after I finished my junior year, I moved into what had been my grandmother’s bedroom.

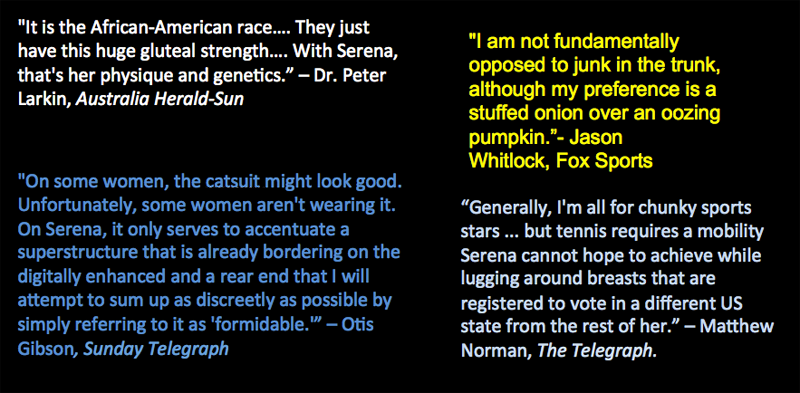

I’d like to start out by laying out a few background statements to take for granted in the interest of time. First, that Serena Williams is a remarkable figure in terms of dominance, significance, and public profile in the sport of tennis. Second, that Williams’ outsized public profile has largely been mediated by photography. And that these photographs have existed within an environment of toxic discourse on Williams’ appearance, in a pattern mirroring that of such other prominent black women as Michelle Obama and Leslie Jones.

I’d like to start out by laying out a few background statements to take for granted in the interest of time. First, that Serena Williams is a remarkable figure in terms of dominance, significance, and public profile in the sport of tennis. Second, that Williams’ outsized public profile has largely been mediated by photography. And that these photographs have existed within an environment of toxic discourse on Williams’ appearance, in a pattern mirroring that of such other prominent black women as Michelle Obama and Leslie Jones.

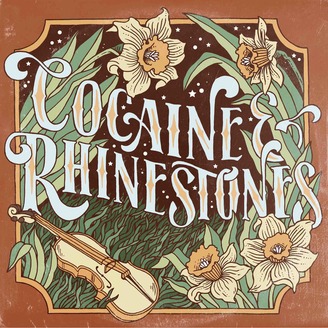

In late 2017, I went on a recommendation spree for Tyler Mahan Coe’s podcast about the history of country music,

In late 2017, I went on a recommendation spree for Tyler Mahan Coe’s podcast about the history of country music,

One of the recurring themes of my adult life has been my getting the itch to go back and take a look at some book or movie or album that I loved when I was younger but haven’t re-engaged with for a while. The vast majority of the time, I walk away from the revisit shaking my head and telling myself that hey, it’s no crime to

One of the recurring themes of my adult life has been my getting the itch to go back and take a look at some book or movie or album that I loved when I was younger but haven’t re-engaged with for a while. The vast majority of the time, I walk away from the revisit shaking my head and telling myself that hey, it’s no crime to

As I write this, it’s June of 2017, which means that I’ve spent at least the last 18 months preoccupied with politics at a level that I’d never matched before; and I was pretty preoccupied with politics before. But now, for me and big chunks of the rest of the country, it’s saturation level.

As I write this, it’s June of 2017, which means that I’ve spent at least the last 18 months preoccupied with politics at a level that I’d never matched before; and I was pretty preoccupied with politics before. But now, for me and big chunks of the rest of the country, it’s saturation level. This was originally written as a paper for an art history class in curation.

This was originally written as a paper for an art history class in curation.

The other night, while cooking dinner, I listened to the Replacements’ Tim. It’s one of those weird cases where Tim’s been one of my favorite albums for decades, but between the march of time, the constant ingress of new music, and my slow disengagement from the practice of listening to albums straight through, it’s actually been years since I’d listened to the whole thing straight through.

The other night, while cooking dinner, I listened to the Replacements’ Tim. It’s one of those weird cases where Tim’s been one of my favorite albums for decades, but between the march of time, the constant ingress of new music, and my slow disengagement from the practice of listening to albums straight through, it’s actually been years since I’d listened to the whole thing straight through.