It always hurts to talk about when one of your heroes fails, but that’s what I’m out to do here. Charles Schulz is one of the great figures in comics; Charles Schulz sometimes fell on his ass. He did here. Acting with well-documented good intentions, he tried to do a good thing, and slid into what could most charitably be called mixed success. By introducing Franklin, a black character, into his immensely popular comic strip Peanuts, Charles Schulz wanted to harness his cultural power and use it to send a positive social message about racial harmony. He explicitly wanted to integrate his strip in a way that wasn’t demeaning or insulting. Thirty years later, though, Franklin was considered one of the prime exemplars of tokenism, a perception that has only grown as time has continued to pass.

Peanuts in 1968 was a cultural juggernaut, appearing in well over 2500 newspapers. In an era when newspaper comics carried a cultural weight nearly unimaginable today, Schulz was at the very top of the profession, giving him one of the most visible platforms in the country to trumpet any message he chose.

For the most part, Schulz avoided politics in the strip, instead examining emotional and existential humor.

The one exception to this aversion to politics is Schulz’s interest in promoting a broad-spectrumed notion of diversity. Peppermint Patty was introduced to the strip in 1966, partly because Schulz wanted to show a character who didn’t conform strictly to established gender norms.

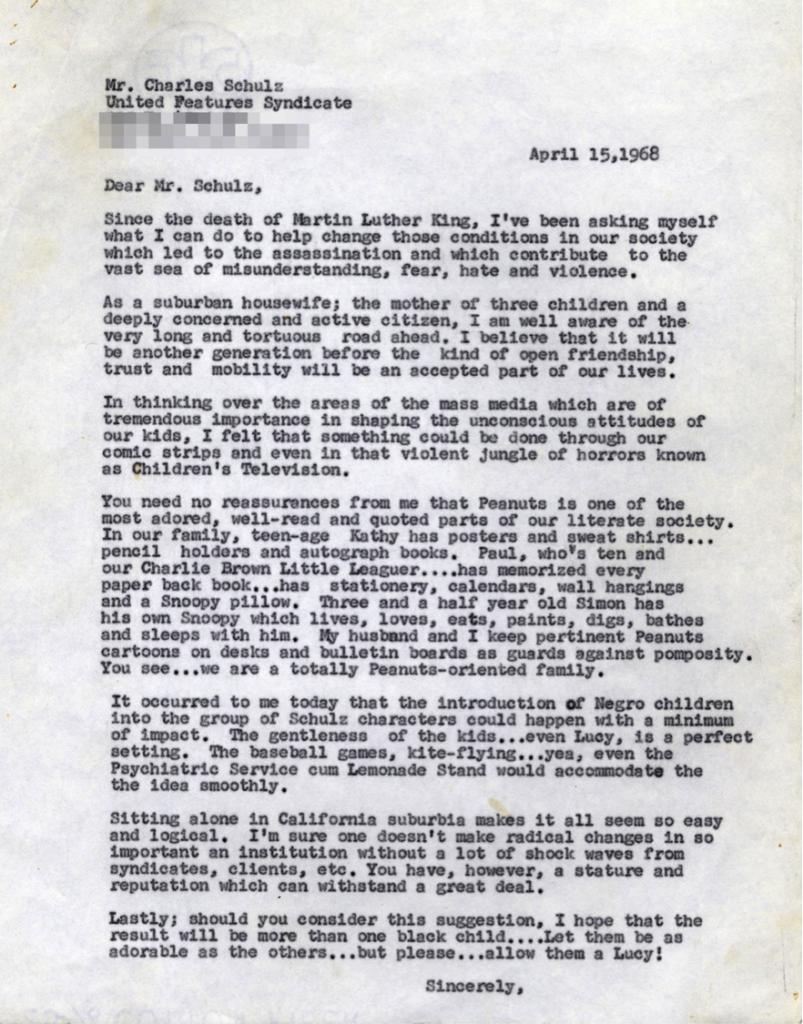

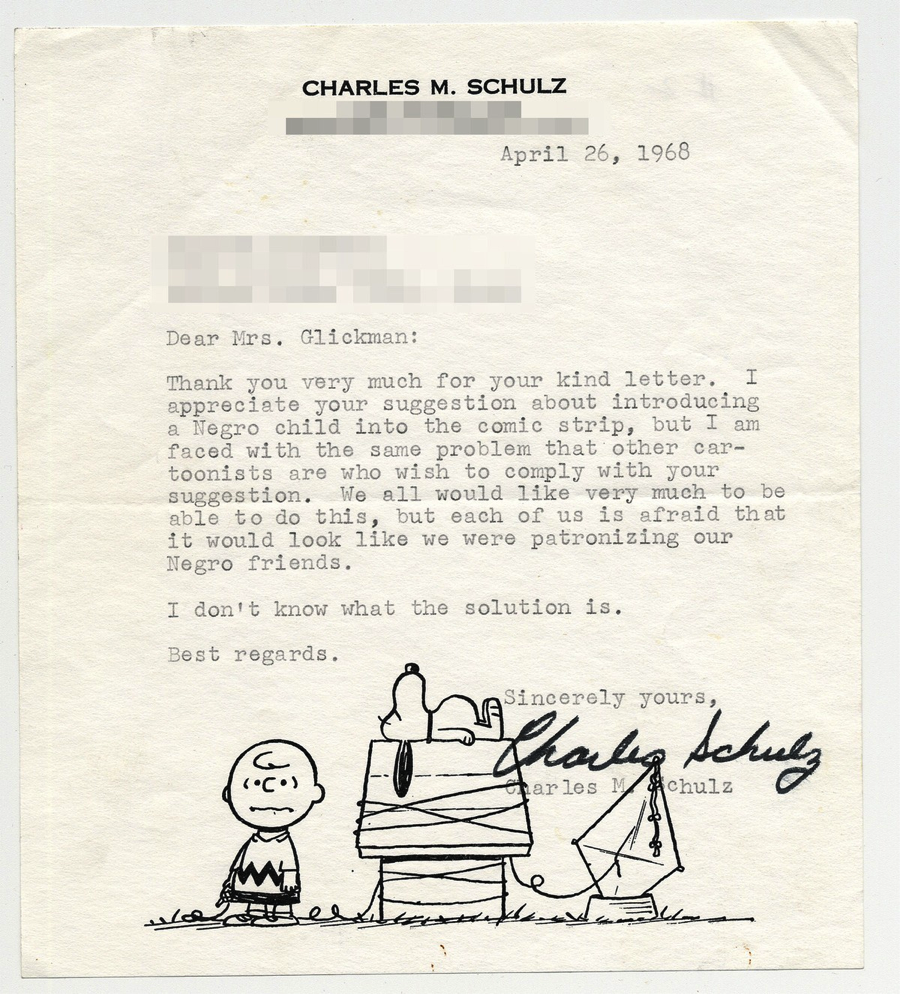

Two years later, this large-hearted agenda manifested again with the introduction of Franklin. The inciting incident was a letter from Harriet Glickman, a fan of the strip, who wrote in April of 1968 suggesting that, in the wake of the assassination of Martin Luther King, Schulz was in a unique position to help heal society by showing black and white children interacting happily. Schulz’s reply is telling: “I appreciate your suggestion about adding a Negro child to the comic strip, but I am faced with the same problem that other cartoonists are who wish to comply with your suggestion. We all would like very much to be able to do this, but each of us is afraid that it would look like we were patronizing our Negro friends. I don’t know what the solution is.”

Glickman didn’t give up, and the two corresponded for months. Schulz was receptive but fearful of appearing condescending, and his repeatedly-stated fear of integrating the strip in a patronizing way is many things: laudable, ironic (given the eventual perception), and, quite possibly, a self-fulfilling prophecy. Glickman went so far as to solicit black friends for positive opinions which she could forward to Schulz.

Schulz was convinced, and wrote a final letter to Glickman telling her that the Peanuts strips running the week of July 29 would have something “I think will please you.”

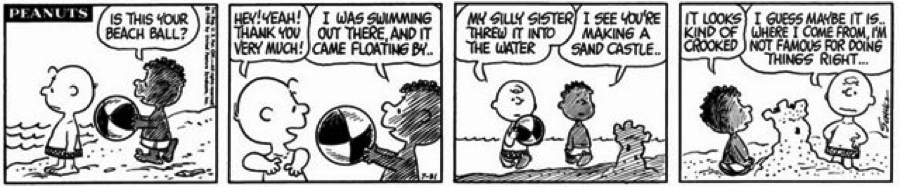

So here we have it. Charlie Brown and Franklin on a beach, hanging out like it’s no big deal.

Now, It’s worth taking a moment here to note a subtle but powerful thing Schulz did to make his point that Franklin and Charlie Brown are the same.

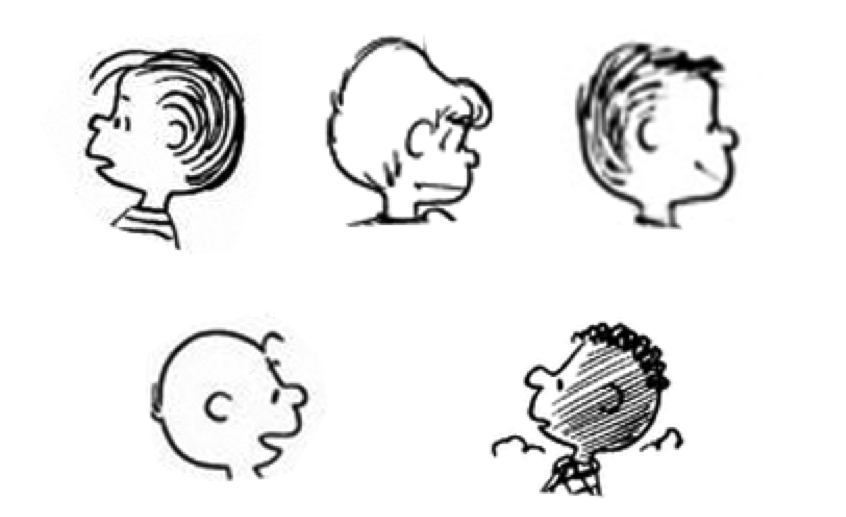

Visually, Charlie Brown is distinguished by his extremely round head (Snoopy’s internal-monologue name for him is “the round-headed kid”). Characters added after the first few years of Peanuts all have heads shaped like exaggerated human skulls, with bulging foreheads and pronounced brow ridges.

Franklin, uniquely, shares Charlie Brown’s ovoid head, with a bit of hair added on top. This congruity, especially expressed though Schulz’s minimal style, speaks volumes, visually underscoring the lack of difference between the two children.

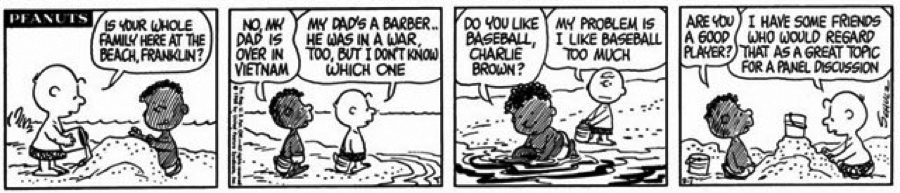

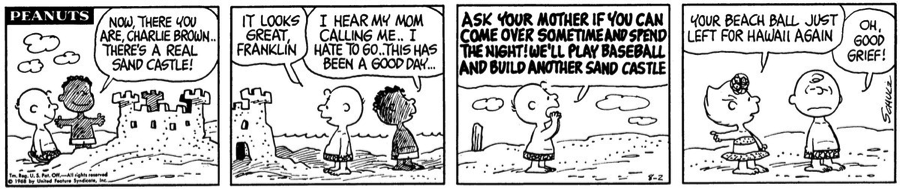

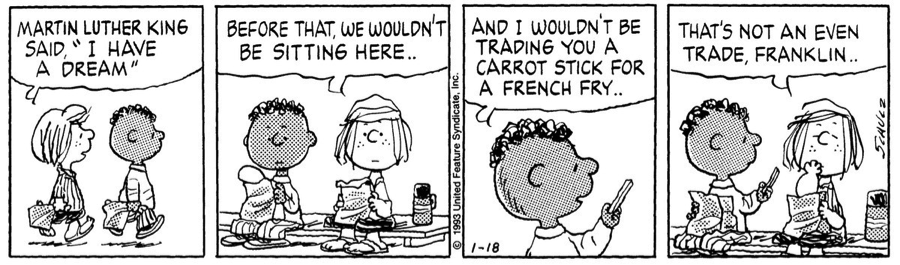

After his introduction, Franklin appeared in Peanuts for the rest of the strip’s run, the only recurring black character. His blackness was explicitly mentioned only a handful of times over these 30 years – one centered on the lack of black players in the NHL (Schulz was a hockey nut), and one more openly acknowledging Martin Luther King and school integration – tellingly, in that strip Franklin deflects the conversation to talk about food.

In the vast majority of the Peanuts strips in which he appears, Franklin serves as the straight man, reacting to the actions of the more neurotic Peanuts characters. As Schulz intended, he’s always hanging out with the cast without comment on his race. He goes to school with Peppermint Patty. He plays sports. He talks philosophy with Linus. He does everything but develop a neurosis that defines his character, the way other major Peanuts characters have.

Not unsurprisingly, given the time, there was pushback to Franklin. In November of 1969, Schulz’s distributor, United Features Syndicate, received this letter:

Gentlemen: In today’s “Peanuts” comic strip Negro and white children are portrayed together in school. School integration is a sensitive subject here, particularly at this time when our city and county schools are under court order for massive compulsory race mixing. We would appreciate it if future Peanuts” strips did not have this type of content. Thank you.

In the face of opposition, Schulz admirably stuck to his guns. When asked by his contact at the syndicate to stop making strips showing Franklin interacting with white characters, Schulz said simply: “Well, Larry, let’s put it this way: Either you print it just the way I draw it or I quit. How’s that?”

OTHER CARTOONISTS

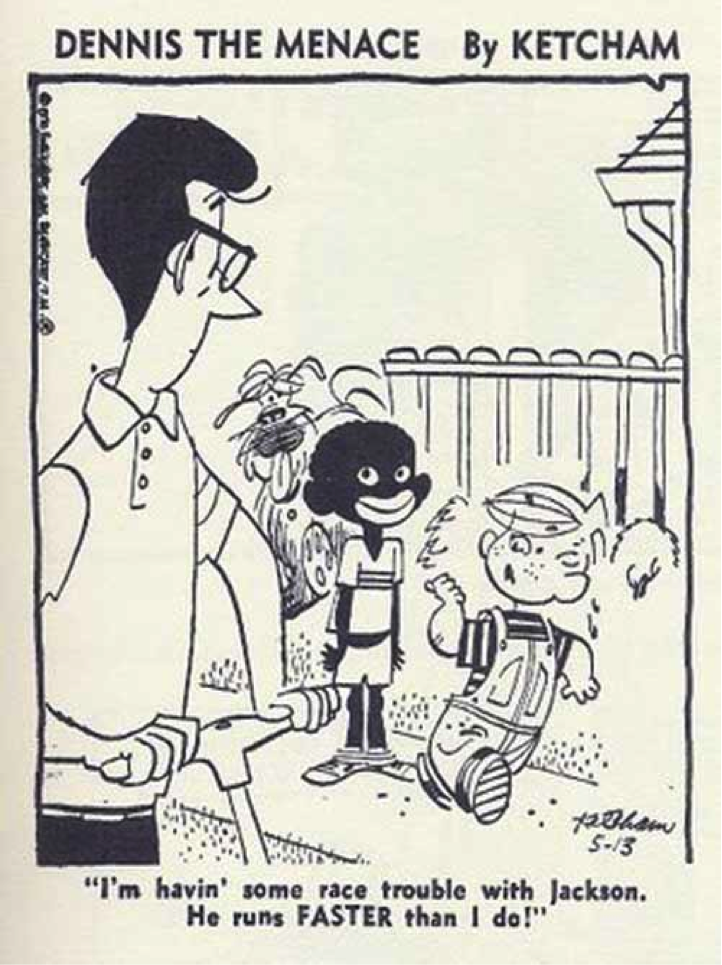

Let’s take a moment and look at how Schulz’s peers were integrating their strips in the late 60s.

This ran on May 13, 1970. The Cleveland Press, at least, had the decency to run an apology for the strip the day after. Amazingly, cartoonist Hank Ketcham didn’t understand why people were offended. Ketcham’s discussion of the strip in his memoir is such a monument of cluelessness that it deserves to be quoted at length, particularly for the contrast it shows with Schulz’s worldview:

Back in the late 1960s when minorities were getting their dander up, painting signs, joining in protest marches, and calling attention to their plight, I was determined to join the parade led by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., and introduce a black playmate to the Mitchell neighborhood. I named him Jackson and designed him in the tradition of Little Black Sambo … He was cute as a button, and, in addition to being a marvelous graphic, he would reflect the refreshing, naive honesty of preschool children. … The rumble started in Detroit, then moved south to St. Louis where rocks and bottles were thrown through the windows of the Post-Dispatch. Newspaper delivery boys were being chased and hassled in Little Rock, and in Miami some Herald editors were being threatened. The cancer quickly spread to other large cities. … I was shocked, then frustrated, then mad as hell. … I made a point not to apologize but to express my utter dismay at the absurd reaction to my innocent cartoon. … It seems that Sammy Davis, Jr., was the only one who could safely poke fun at the minorities. To this day, Jackson remains in the ink bottle. A pity.

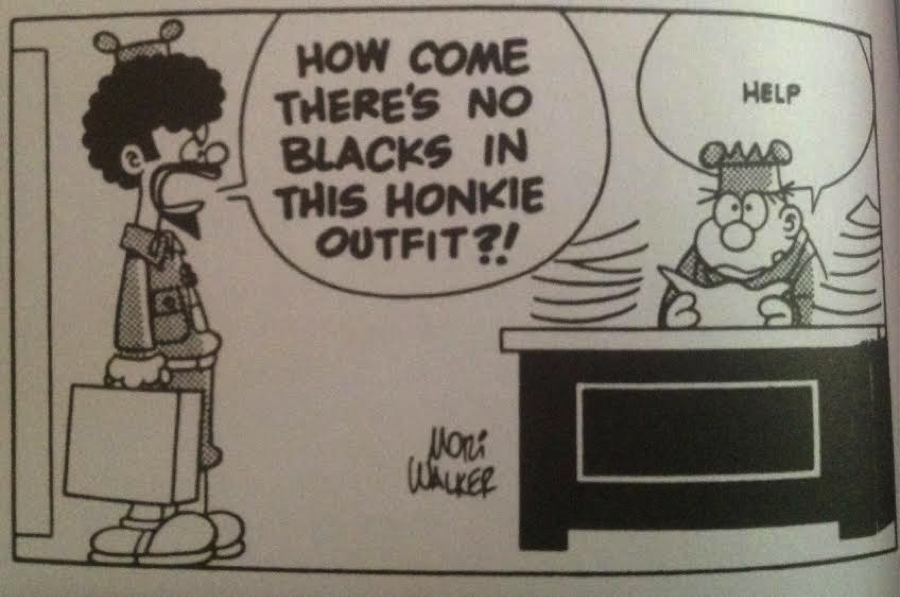

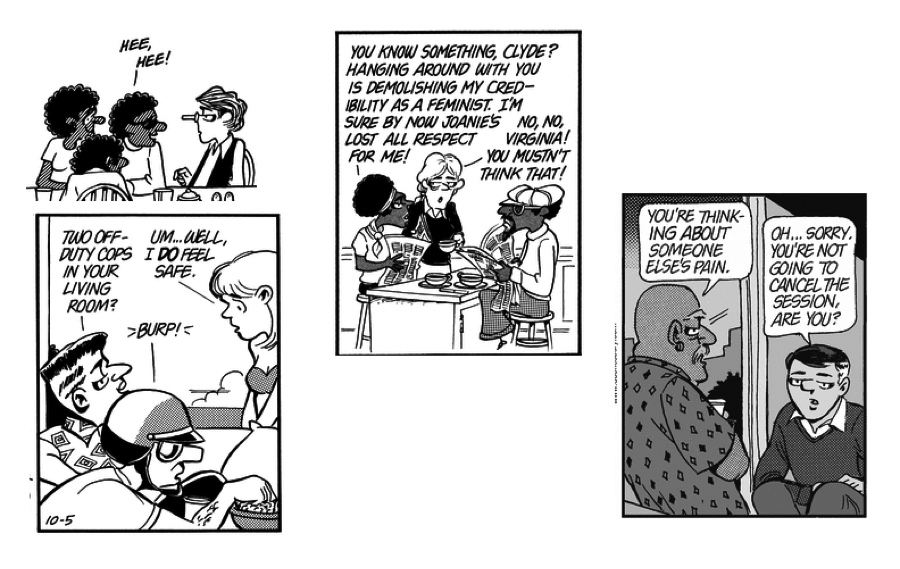

Starting October 5, 1970, Lt. Jack Flap began appearing in Mort Walker’s Beetle Bailey.

Again, the “success” of the integration speaks for itself. I should add here that as late as 1990, Walker would be adding a representative “Asian” character with slanted lines for eyes.

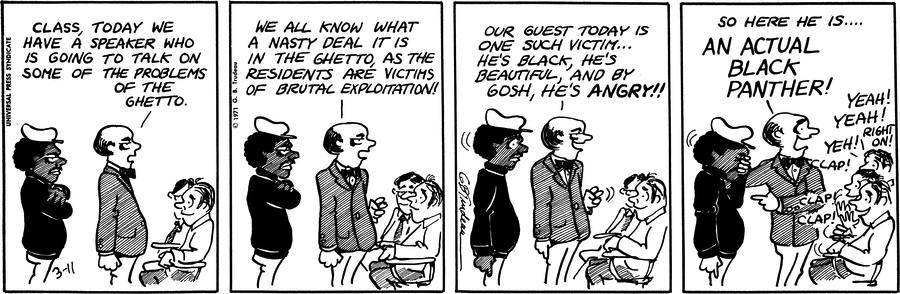

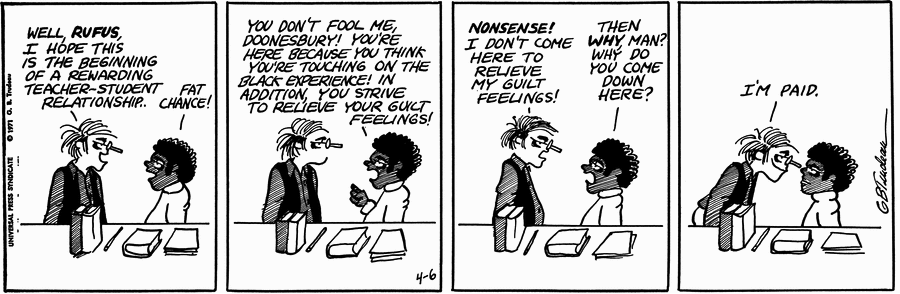

On the other end of the social engagement spectrum was Garry Trudeau’s Doonesbury. Unlike Schulz, Trudeau was happy to directly engage in political and social commentary, and was quick to integrate his strip’s initial cast of effete middle-class white college students.

Trudeau’s first recurring black character is a Black Panther named Calvin. In direct opposition to Schulz’s low-key introduction of Franklin, Calvin’s first appearance includes a metajoke about the previous whiteness of the strip; Trudeau actually goes so far as to draw, in the final panel, Calvin wincing in reaction to his role as the strip’s representation of black America.

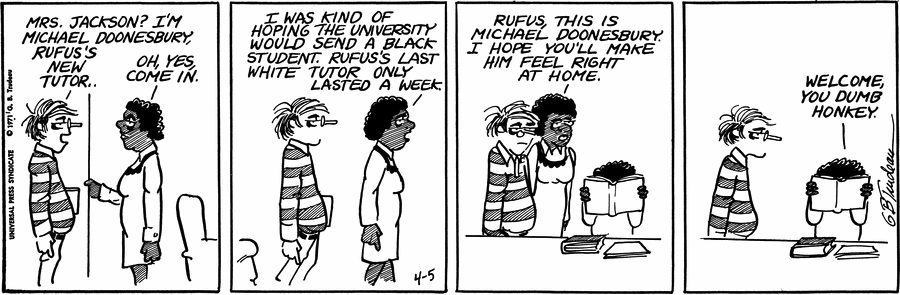

On April 5, 1971, two new black characters show up – a child named Rufus, whom Mike Doonesbury is tutoring, and his phlegmatic mother. Again, the initial strips directly engage in jokes about racial tension

Black characters, both major and minor, appear with regularity through the 70s and on to the current day. They include self-segregating college students, a politically active law student and her leech of a boyfriend, a cop who joins the army, and a PTSD counselor.

SCHULZ OVER THE LONG HAUL

But back to Schulz and Franklin. As established, Franklin was added to the strip in 1968 explicitly to add diversity and send a message to Schulz’s audience. He appeared regularly in the strip through the 70s and 80s, interacting seamlessly with the white cast members as Schulz intended.

Let’s jump to the early 90s.

Chris Rock was then a rising star in comedy, on his way to becoming one of the most prominent black voices in American popular culture. On Saturday Night Live’s Weekend update for September 26, 1992, Rock delivered this monologue:

I hated school, because I was the only black kid in my grade. The whole grade! I felt like Franklin from the Charlie Brown Show. You ever see Franklin? 25 years, not one line. Nothing! 25 years, man! You know everybody’s got their own little character. You know, Linus has the blanket, Lucy’s a bitch, Schroeder plays the piano, Peppermint Patty’s a lesbian. Everybody’s got their thing. Give him something, damn, give him a Jamaican accent or something, ‘C’mon Charlie Brown leave me alone.’ 25 years man, and they never even invited him to the parties. No, but Snoopy’s dancing his ass off.

I’ll be pedantic here and point out that Franklin is invited for dinner in the Charlie Brown Thanksgiving TV special, but Rock’s larger point stands. And he was far from the only person making this observation.

John McWhorter, a Berkeley professor writing about tokenism in entertainment for the LA Times, opened an editorial titled “Black isn’t a personality trait” with a complaint about Franklin almost identical to Rock’s, concluding:

Overall, Franklin had no personality traits at all. Beyond the tint required to render his skin tone, Franklin was a blank. Schulz meant well. But Franklin was a classic “token black,” and that era saw more than a few Franklins.

After Schulz’s death in 2000, the Chicago Tribune’s Clarence Page wrote a combined appreciation of Schulz and lament that now there would be no chance for Franklin to actually develop a character flaw. Page notes, “Even the official “Peanuts” Web page confirms that Franklin’s distinguishing traits are his absence of anxieties or obsessions. What an irony. The comics world finally gets a “Peanuts” character of color and he is not allowed to be the butt of risky humor.”

Page then extends some empathy towards Schulz:

But considering the hyper-sensitivities so many people feel about any matters involving race, I did not blame Schulz for treating Franklin with a light and special touch.

Can you imagine Franklin as, say, a fussbudget like Lucy? … Self-declared image police would call for a boycott. If Schulz’s instincts told him his audience was not ready for a black child with the same complications his other characters endured, he probably was right.

Let’s keep Page’s empathetic response in the back of our minds as we take a look at tokenism as a phenomenon. To establish a baseline, Norma Ricucci in the Encyclopedia of Race and Racism defines tokenism as “the practice or policy of admitting an extremely small number of members of racial, ethnic or gender groups to work, educational, or social activities to give the impression of being inclusive, when in actuality these groups are not welcomed.”

At first, it appears that the question of how well Ricucci’s definition maps to Franklin hinges on intention. Charles Schulz’s correspondence and public statements indicate that he didn’t want to merely give the impression that the hostile environment of the comics page was now inclusive – he genuinely wanted to make it so. But his execution fell short in such a way as to obscure that desire. When a large portion of the public – especially the black public – perceives Franklin as a frustrating, insufficient cipher, that widespread perception means something. Tokenism is most revealed in the eye of the tokenised.

Ricucci’s concept of tokenism is more obviously concerned with the real world, not art or entertainment. And it’s not a stretch to argue that tokenism in the workplace is much more damaging than tokenism in a cartoon. But tokenism in art does matter and is damaging. It marginalizes the tokenized minority, and reinforces their marginalization in the broader culture. It also, intentionally or not, sense a false message that problems of inclusivity have been taken care of and no longer need to be of concern – what do you mean, the country’s has trouble coming to grips with the legacy of slavery? There’s a black kid hanging out with Charlie Brown!

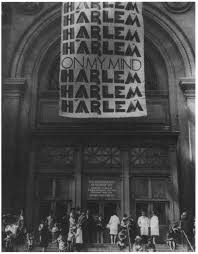

Hopping genres, this situation reminds me quite a bit of the notororious “Harlem on My Mind” exhibit at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. As described in Bridget Cooks’ Exhibiting Blackness, this was an exhibit the Met staged in 1969, intended to “explore the cultural history of the predominantly Black community of Harlem.” It was the Met’s first attempt at a show highlighting black culture. However, the show was a notorious failure because of the Met’s near-total exclusion of any African Americans from the planning process and the bizarre, patronizing tone of the resulting show – which did not include any actual art, consisting instead of wall-mounted photographs documenting life in Harlem.

The parallels to Schulz and Franklin are striking. Well-intentioned white people with prominent cultural platforms making a sincere effort to do right by the African-American community and failing because of the narrowness of their vision. Two things become apparent from these congruent situations: First, that it’s a difficult thing for a member of a majority culture to have a properly broad perspective from which to portray the experience of a minority culture without being reductive or patronizing. And second, that good intentions aren’t enough. Well-intentioned acts done badly can be hard to distinguish from intentionally damaging ones.

Complaints about Franklin as a token stem from two elements: his status as the only black character in the strip, and his uniqueness as a bland straight-man in a cast of neurotics defined by their faults. The former situation, frankly, remains inexplicable to me. If we take Schulz at his word that Franklin was added to the strip specifically to show that black kids and white kids could spend time together without tension, it is odd that it never occurred to Schulz to add other black characters. Maybe he really never did think of it; maybe he was gun-shy after the fights with readers and syndicate from Franklin’s introduction. To my knowledge, Schulz never publicly addressed this decision.

The latter problem, Franklin’s perceived blandness, is much easier to square with Schulz’s public statements, if still frustrating. Franklin’s lack of a defining neurosis stems directly from Schulz’s desire to do right by the black community, to avoid looking, as he wrote to Glickman “like we were patronizing our Negro friends.”

Schulz elaborated on this in a 1988 interview with Michael Barrier: “I’ve never done much with Franklin, because I don’t do race things. I’m not an expert on race, I don’t know what it’s like to grow up as a little black boy, and I don’t think you should draw things unless you really understand them.” For all of the good intentions present with his creation, Franklin was an element in the strip that Schulz didn’t know how to use properly. Because of Schulz’s hesitancy to give Franklin a defining neurosis for fear that it would be read as representative of all of black America (a problem exacerbated by Franklin’s status as the only black cast member) Franklin’s character really does wind up being reduced to “he’s black.” Chris Rock was dead right.

It’s ironic, too, that Schulz had added one other character with a diversity agenda in mind: Peppermint Patty, who is commonly perceived as existing to show that it’s OK for children to defy gender norms. Peppermint Patty’s entire personality, and the humor of many of the strips in which she appears, stems directly from Schulz skillfully examining the problems she has straining against mainstream postwar notions of femininity. It’s frustrating to imagine what Schulz could have done by actively engaging Franklin’s status in the same way.

Compare this with Doonesbury. Several of Trudeau’s strips with black characters, particularly the very early ones, skate to the edge of being problematic by modern standards. But Doonesbury is not widely considered to be a strip that has serious problems dealing with race. Trudeau has introduced a small army of characters who are black. Some are noble and admirable; most are flawed and venal. But nobility and venality are distributed among them in the same proportions as in the strip’s white cast.

One could not, when talking to someone about the strip, refer to anyone as “the black Doonesbury character” and be understood. The fact that Franklin is synonymous with “the black Peanuts character” is testament to the sad fact that Charles Schulz’s execution fell short of his intentions, no matter how noble they were.

Jesus I have a hard time believing that Dennis the Menace panel is from 1970 and not 1930.

I still feel a shock every damn time I see it, and I must have seen it 50 times now.

This is a great article – well structured, balanced, well argued and importantly educational. Thank you! I’m adding this to my arsenal of educational pieces I advise people to read.

I have never thought of Franklin as a token. I just thought of him as another kid who happened to be black; which was essentially the point Schulz was trying to make. Not too long after this strip ran I first attended a summer camp that had black kids. My southern parents wouldn’t allow me to play with black kids who’d moved into our neighborhood but at summer camp it was different. On my first day I was trying to put on clip on roller skates and two little boys came to help me get them on my shoes securely. They were both black, Eugene and Melvin. They were so worried the skates would come off and I’d fall so they made extra sure they were on tight. They were the nicest little boys I’d ever met and I loved them right away. They, like most of the other kids at this camp, were private school kids just like me. They were both super smart too. I went home and had a fit to my parents. I said, “you lied to me they’re just like me!” My parents had no black friends and therefore no frame of reference, only what they’d been taught by their parents, who also had no black friends. Eugene’s dad was a dentist. Melvin’s father was a real estate professional. My home town of Birmingham had lots of wealthy black people in it and all of their kids went to my summer camp. So my parents retreated and watched me go through life as a champion of civil rights. I heard lots of bad things said about black people along the way but never without speaking up. My mother’s best friend at the time of her death was a black woman. Her last presidential vote was cast for Barack Obama. My mother got there because I got there quick when I was 11 years old at summer camp. She saw my friends come and go at our house, many of them black children. She always marveled that I had the most wonderful friends. I am still the same person I was at 11. Eugene died a couple of years ago but Melvin and I are still friends. We have always loved each other dearly. My little brother and I read Peanuts comic books all the time and loved them. What Schultz said was exactly what needed to be said; Franklin was just another kid who happened to be black. That was the single most important thing to say. We all cry when we’re sad, we all get angry sometimes, we are all happy sometimes. We are, at our cores, the same eating, breathing, feeling beings. It doesn’t matter if we are black, brown, or white. Franklin was not a token. in later years there were lots more black children in the crowds of Peanuts characters. Schultz focused on his principal characters but he made sure we saw some color. He made a difference with Franklin, a big one.