ABOUT THE PROJECT:

I’ve had the itch lately to get back into the writing/blogging game, but couldn’t find an angle. I’ve also been thinking a lot about movies lately as (maybe until pretty recently) the great unifying American artform (not in the sense that all movies are American, but in the sense that for about the last hundred years at least, movies are one of the dominant ways that Americans as a body interact with art). But there’s enough writing and talking about movies already, I thought, listening to a podcast that’s essentially a game show of movie rankings; who needs any more?

But then it hit me that the magical thing about all art is that it sort of has multiple existences—the single, standalone objective work on its own in a vacuum, and then the subjective experience when an individual person actually encounters it. And maybe my subjective encounters with movies are worth writing about.

So: I’m gonna do the full subjective journey, picking a movie that came out in each year of my life and writing about it. I imagine these’ll go all over the place in terms of approach, polish, and length. With this many entries to write (I’ve been alive a lot of years), variety’s the only way to keep it going.

SO LET’S GET ROLLING

1974: THE BIG SWINGS OF ZARDOZ

Zardoz (dir. John Boorman)

I was originally going to write about Blazing Saddles for 1974, because it was a profoundly formative movie for me, thanks to my parents’ insanely lax standards for what I could watch when I was a kid; but I remembered that I already wrote about it at some length in terms of it being a surprising example of postmodernism.

So instead, let’s talk about Zardoz.

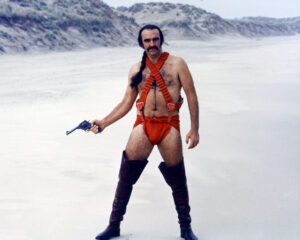

Zardoz has served as a punchline as long as I’ve been aware of it. And I get it, I do. People tend to experience the movie first through pictures of Sean Connery in costume and yeah, it’s a ridiculous costume. The movie’s full of preposterous over-the-top moments, like when the room full of anhedonic future lotus-eaters are shocked by a boner. There’s a giant stone head that floats around the countryside vomiting guns and shouting about the penis.

And yeah, maybe all that stuff is preposterous. But it’s also audacious as hell, and that’s what I love about Zardoz. On both philosophical and visual levels, this movie is just Boorman taking huge swing after huge swing, and I don’t know how you can’t at least respect that. For my money, the visual swings connect more than the philosophical; go back to the floating head vomiting guns. How can you deny that as an iconic, arresting image? That’s the kind of entire-gigantic-ball-of-experience-tied-into-one-image work that we usually associate more with Kubrick or Lynch. And Connery’s costume: it’s silly, but it persists in a way that a lot of other silly costumes don’t; it’s at least extremely memorable and striking in its silliness. Not all of the visual swings land—there are some stretches where the movie does just look like people in dated costumes running around on a set—but enough of them do to swing the balance hard in the movie’s favor.

The philosophical swings? Well, that’s more of an “I admire the effort” situation. The twist reveal that “Zardoz,” the name of the giant head that’s been ordering around the population of “Brutals,” is taken from The Wizard of Oz isn’t profound, but it’s fun. The bigger philosophical arc of the movie is… not great, but it’s interesting. That arc: it’s the far future, and humanity has split into two populations. There are the Brutals, who live in a postapocalyptic wasteland and mostly spend their lives in subsistence toil unless they’re a member of the Zardoz-led Exterminator bands like Sean Connery’s character Zed; and then there are the Eternals, who live a perfect, cossetted existence in a hidden compound free of conflict or want, ruled over by an AI.

Those Eternals, the movie posits, are atrophying away because their existence is *too* cossetted. They have no vitality (this is why they’re shocked by a boner), and they risk lapsing into catatonia. The movie serves as an extended argument that they *need* the rough rawness of Connery’s Zed to shake them up and restore some balance and zip to them.

Every movie is fundamentally making some kind of argument; “cossetted people will lose their vitality and need to have their drink stirred by a rough-ass dude” isn’t a super compelling one, as filmic thesis statements go. But I feel like it’s a weirdly persistent one in science fiction; think of how many pre-Star Wars SF movies revolve around “perfect” societies that have gotten dull and stultified and need to be shaken up. Or post Star Wars, too—this is explicitly the plot of Demolition Man and serves as the (unfortunate, godawful) diagetic explanation for all of the Khan nonsense in Star Trek Into Darkness. So even if I don’t share it, I guess a lot of people operate on some level of worry that humanity is going to stultify ourselves if we make a better society. You probably don’t have to look too hard there to see a reactionary distrust of social progress (for an opposing view, take a look at Iain M. Banks’ Culture novels, a great body of science fiction that argues that living in a progressive post-scarcity society would be rad as hell while still offering plenty of chances to be vivid and experience life).

Anyway, in terms of Zardoz’s argument for getting out there and enjoying life on raw biological terms, I guess I need to point out that I did the math and, well, it was in theaters when I was conceived. Make of that what you will, I guess.

I can’t argue that Zardoz is a *great* movie, but it’s one that I have a lot of affection for. It’s one that I kind of simultaneously laugh at and with while I watch it. It’s a product of the era of science fiction where movies tried to grapple with big ideas and show people things they hadn’t seen before. And if it doesn’t really do much on the grappling-with-ideas front, it sure as hell succeeds on showing us something we’d never seen before, or since.

Nice, glad to see you back! 🙂 On the topic of cossetted weaklings in the perfect future, I always kind of thought this was an argument by the haves telling us have-nots that all the suffering we are enduring to ensure their life of leisure is actually good for us. Like, oh sure I am day drinking by the pool all day while you are dying in the mines, but you are the one who is really living.

Thanks! And I think you’re *absolutely* onto something there.

When I got to the “cossetted people will lose their vitality and need to have their drink stirred by a rough-ass dude” part I was certain a we were headed for a quick detour through Rush’s 2112.

You showed great restraint.

oh SHIT, that wasn’t restraint, that was raw forgetfullness