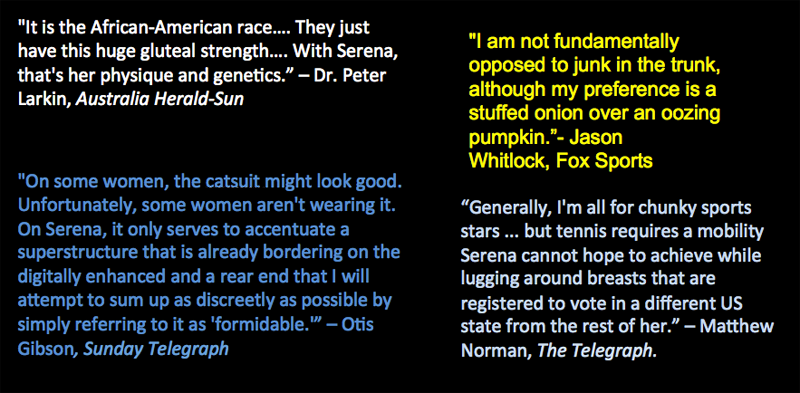

I’d like to start out by laying out a few background statements to take for granted in the interest of time. First, that Serena Williams is a remarkable figure in terms of dominance, significance, and public profile in the sport of tennis. Second, that Williams’ outsized public profile has largely been mediated by photography. And that these photographs have existed within an environment of toxic discourse on Williams’ appearance, in a pattern mirroring that of such other prominent black women as Michelle Obama and Leslie Jones.

I’d like to start out by laying out a few background statements to take for granted in the interest of time. First, that Serena Williams is a remarkable figure in terms of dominance, significance, and public profile in the sport of tennis. Second, that Williams’ outsized public profile has largely been mediated by photography. And that these photographs have existed within an environment of toxic discourse on Williams’ appearance, in a pattern mirroring that of such other prominent black women as Michelle Obama and Leslie Jones.

While Serena Williams has always had a public persona that was largely shaped by images, the late phase of her career is marked by her exercising increasing levels of agency to curate this persona in a manner that’s consistent with the principles of third-wave feminism. This is happening in the face of an existing discourse on her and her body that’s deeply troubling on axes of both her gender and her ethnicity. A close examination of the photographs used in her appearances on the cover of Sports Illustrated–as well as those of her peers–gives us a good window through which to take a look at this phenomenon.

As the illustration above shows, I think the point is made about the toxic discourse. As tempting as it is to catalogue the mind-blowingly offensive commentary directed at Serena Williams for the crime of being a muscular black woman who’s surpassingly good at a historically white sport, that’s not exactly why we’re here. Instead, I just wanted to give you an idea of the context in which any photo of Serena Williams exists. With that established, I’d like to start talking about Sports Illustrated.

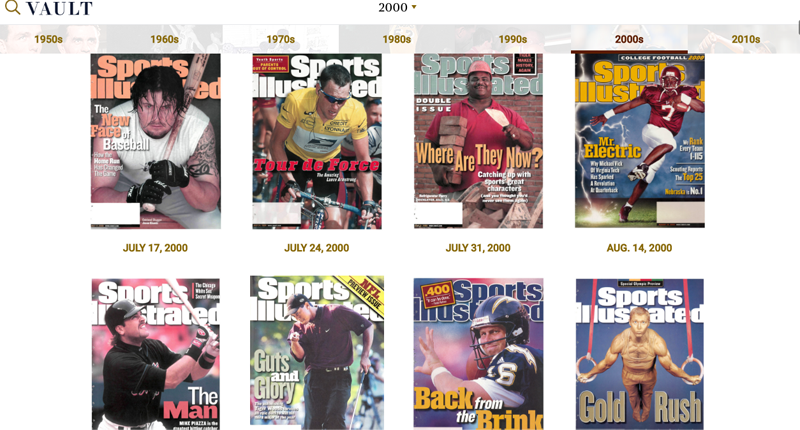

Sports Illustrated has been around since 1954 and serves, I’d argue, as a good synecdoche for mainstream, mass-market sports interest in the United States (and by transference, for a decent-sized chunk of American mass culture, especially white male culture).

Sports Illustrated has been around since 1954 and serves, I’d argue, as a good synecdoche for mainstream, mass-market sports interest in the United States (and by transference, for a decent-sized chunk of American mass culture, especially white male culture).

Sports Illustrated publishes about 48 issues a year, give or take, and each issue’s cover is composed around a photograph. Each cover image represents what Sports Illustrated’s editorial team thinks best represents the confluence of what’s happening in sports at that moment and what will entice the American public to buy a magazine.

While researching this piece, I looked at every Sports Illustrated cover since the mid-1990s. While doing so, I detected a lot of patterns; enough so that I feel comfortable formulating some laws of Sports Illustrated Cover Photography.

The first law: the vast majority of cover photographs will be of men. In any given year, there will be pictures of women on the cover of the swimsuit issue and then maybe four or five other covers in a busy year. There are years when Brett Favre appears on more covers than an entire gender.

Next: These photos of men will usually show them in action. If not in action, then posing in their uniform. Rarely- usually if someone’s being singled out for some honor, or if they’re a sports-adjacent figure who doesn’t compete – they’ll be shown posing in non-sporting clothes.

Next: These photos of men will usually show them in action. If not in action, then posing in their uniform. Rarely- usually if someone’s being singled out for some honor, or if they’re a sports-adjacent figure who doesn’t compete – they’ll be shown posing in non-sporting clothes.

The rules are a little different for women, in their handful of cover photos. We’ll set aside the swimsuit issue, because it’s its own thing with its own rules.

White women with blonde hair follow a specific pattern. These photos are generally not action shots; or if they are, they’ll be action shots that emphasize the women’s bodies. In posed shots, they often will not be wearing their competition uniforms. Anna Kournikova here is wearing street clothes and gazing directly but softly at the camera. She’s leaning across and hugging a pillow. Jennie Finch’s clothing is vaguely softball-y, but her pose and demeanor are nothing you’d see in a cover picture of a male athlete. Maria Sharapova’s on a tennis court, but shot from an angle that maximizes how much of her upper thigh you see, and she’s pulling a ball out of her shorts. Recognizing that this is a subjective, loaded term, I’d be comfortable labelling these images as sexualized.

White women with blonde hair follow a specific pattern. These photos are generally not action shots; or if they are, they’ll be action shots that emphasize the women’s bodies. In posed shots, they often will not be wearing their competition uniforms. Anna Kournikova here is wearing street clothes and gazing directly but softly at the camera. She’s leaning across and hugging a pillow. Jennie Finch’s clothing is vaguely softball-y, but her pose and demeanor are nothing you’d see in a cover picture of a male athlete. Maria Sharapova’s on a tennis court, but shot from an angle that maximizes how much of her upper thigh you see, and she’s pulling a ball out of her shorts. Recognizing that this is a subjective, loaded term, I’d be comfortable labelling these images as sexualized.

Anyway. That’s blonde white women.

Black women – and to a large extent, dark-haired white women – follow the same general rules as male athletes- action shots, mostly, not showing or emphasizing any more of their body than you’d see in competition, usually wearing their competition gear and either not making eye contact with the camera or maintaining a neutral gaze if they do.

Black women – and to a large extent, dark-haired white women – follow the same general rules as male athletes- action shots, mostly, not showing or emphasizing any more of their body than you’d see in competition, usually wearing their competition gear and either not making eye contact with the camera or maintaining a neutral gaze if they do.

Serena Williams’ cover appearances generally conform to these laws. (and it’s worth pointing out, by the way, that she is pretty much the only woman you can do this sort of comparison with, since in the period I surveyed, she’s the only woman to appear more than twice on non-swimsuit SI covers). September 1999 she has an action shot. May 2003, another action shot. It does emphasize her musculature, but in a way similar to the way they photograph male athletes. July 2010- action shot, and a pretty intense one. August 2015, a pretty magnificent action shot as she’s in the process of serving.

Serena Williams’ cover appearances generally conform to these laws. (and it’s worth pointing out, by the way, that she is pretty much the only woman you can do this sort of comparison with, since in the period I surveyed, she’s the only woman to appear more than twice on non-swimsuit SI covers). September 1999 she has an action shot. May 2003, another action shot. It does emphasize her musculature, but in a way similar to the way they photograph male athletes. July 2010- action shot, and a pretty intense one. August 2015, a pretty magnificent action shot as she’s in the process of serving.

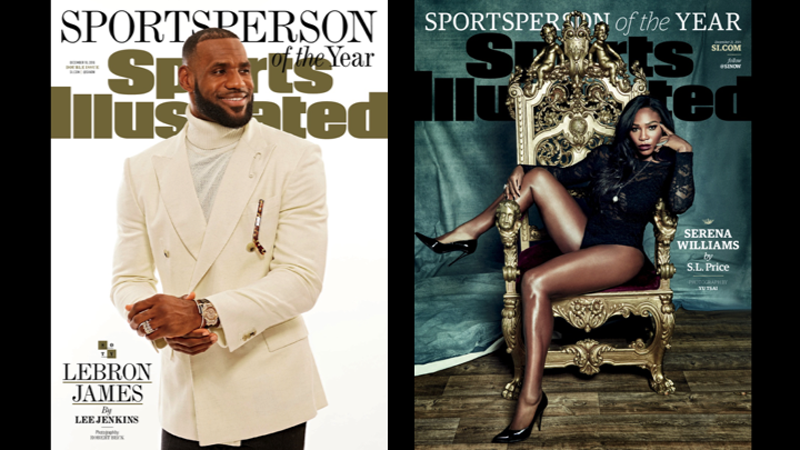

And then there’s Williams’ cover photo in December of 2015, when she was named Sportswoman of the year.

I’d seen this picture before, but I was still startled when I got to it going through the Sports Illustrated archives, because it’s such a departure from the firmly-established patterns, especially for Serena Williams. It’s posed, not an action shot. She’s wearing a bodysuit and stiletto heels, and is posed in a way that highlights her legs. By the standards I laid out before, this is a sexualized photograph, in a way that none of their previous photographs of Serena Williams have been.

I’d seen this picture before, but I was still startled when I got to it going through the Sports Illustrated archives, because it’s such a departure from the firmly-established patterns, especially for Serena Williams. It’s posed, not an action shot. She’s wearing a bodysuit and stiletto heels, and is posed in a way that highlights her legs. By the standards I laid out before, this is a sexualized photograph, in a way that none of their previous photographs of Serena Williams have been.

But even if this photograph has some categorical similarity with the previous Kournikova photo, I think there’s something different going on here. Kournikova’s posed with a soft gaze, hugging a pillow, looking slightly up at the viewer. Williams is lounging on a throne. I’d argue that the look on her face, combined with the hand on her face, communicate a look of judgment. The power dynamics in the two photographs are completely different.

This is a bit subjective, but I’d argue that LeBron James’ cover photo, a year later when he’s named Sportsperson of the Year, doesn’t communicate nearly as much interpersonal power as Serena Williams’ throne picture does. James is relaxed, looking away from the camera, and looks just sort of bemused rather than sternly judgmental.

This is a bit subjective, but I’d argue that LeBron James’ cover photo, a year later when he’s named Sportsperson of the Year, doesn’t communicate nearly as much interpersonal power as Serena Williams’ throne picture does. James is relaxed, looking away from the camera, and looks just sort of bemused rather than sternly judgmental.

So what’s going on here with this picture, which was taken, by the way, by Yu Tsai? It’s important to note another thing about the picture: it was William’s idea, and her choice.

Again, there’s subjectivity here, but if we think back to the covers with Jennie Finch and (especially) Anna Kournikova, there’s certainly an argument to be made that they’re exploitative. The composition and framing of all three covers imply that the camera is ogling the subject, in a manner that casts them as subservient. The Williams cover, by contrast, communicates that the camera has been summoned to appear before a monarch. If this is a sexualized picture, it’s one that’s different because all of the implied power rests with the person in the sexualized picture.

Again, there’s subjectivity here, but if we think back to the covers with Jennie Finch and (especially) Anna Kournikova, there’s certainly an argument to be made that they’re exploitative. The composition and framing of all three covers imply that the camera is ogling the subject, in a manner that casts them as subservient. The Williams cover, by contrast, communicates that the camera has been summoned to appear before a monarch. If this is a sexualized picture, it’s one that’s different because all of the implied power rests with the person in the sexualized picture.

A BRIEF DETOUR INTO THE HISTORY OF FEMINISM

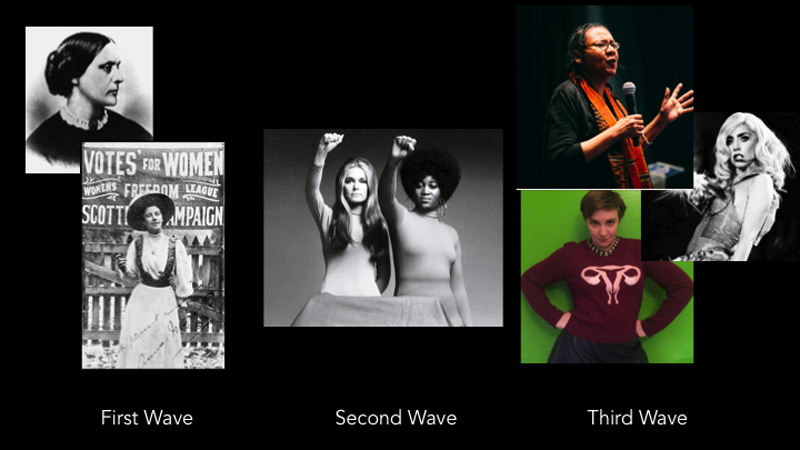

Let’s take a break here and talk about a simplified history of feminism. I know that it’s a queasy activity for a white man to start rambling about the history of feminism; I’ll just ask you pre-emptively–and sincerely–to let me know in the comments if you have any disagreements or quibbles.

As I understand it (and believe me, I know that I’m compressing and simplifying a lot of things here for the sake of brevity), Feminism in the modern, western world comes in three distinct phases. For first-wave feminism, you can think Susan B. Anthony and the Suffragists. This wave, extending from the 19th into the first half of the 20th century, was basically concerned with essential legal rights- being able to vote, being able to own property, being recognized as full humans by the law.

As I understand it (and believe me, I know that I’m compressing and simplifying a lot of things here for the sake of brevity), Feminism in the modern, western world comes in three distinct phases. For first-wave feminism, you can think Susan B. Anthony and the Suffragists. This wave, extending from the 19th into the first half of the 20th century, was basically concerned with essential legal rights- being able to vote, being able to own property, being recognized as full humans by the law.

Second wave starts mid 20th century- think Gloria Steinem, Dorothy Pittman-Hughes, the book The Feminine Mystique, and so on. Again, greatly simplifying, the second wave looked to deal with inequalities that often weren’t directly coded in law but were instead immediate consequences of legal and social structures: the wage gap. Reproductive rights. Domestic violence. Broadly speaking, the second wave extended into the 90s and saw figures such as Andrea Dworkin and Camille Paglia hotly debating the boundaries of sex in all of this.

Third-wave feminism is where we’re at now. Historically speaking, it’s always hardest to categorize the moment you’re living in. But what matters to us here is that third-wave feminism is concerned with the intersection of discrimination based on gender with discrimination on other fronts- such as race- and with sex-positivity and a woman’s agency over her own body. As Jed Woodworth argues in the book Culture Wars in America, third-wave feminists “argued for the liberation of female individuality—in sexual identity, above all—free from the constraints of [second-wave feminist] politics.” As it was explained to me, third-wave feminism is the space in which Lady Gaga, bell hooks, and Lena Dunham can all coexist as prominent feminists in eye of some portion of the public.

Which brings us back around to Serena Williams on her throne, in a photo she chose, putting her body on display while also directing the power dynamics to her. This photograph in this context, I’d argue, is about as pure an expression of third-wave feminism as you can find. It’s not that her previous SI cover photographs were offensive, dismissive, or exploitative in any way; but they weren’t as remarkable as this one, nor as demonstrative of an identity beyond “good tennis player.” And this isn’t an isolated incident in the current phase of Serena Williams’ public career.

The same month this issue of SI hit the newsstands, a nude photo of Williams, taken by Annie Liebovitz, appeared in the 2016 Pirelli Calendar. This calendar, which also included Liebovitz photos of Amy Schumer, Ava DuVarnay, Yoko Ono, and Patti Smith, was promoted as an attempt to deconstruct the old tradition of girlie calendars.

The same month this issue of SI hit the newsstands, a nude photo of Williams, taken by Annie Liebovitz, appeared in the 2016 Pirelli Calendar. This calendar, which also included Liebovitz photos of Amy Schumer, Ava DuVarnay, Yoko Ono, and Patti Smith, was promoted as an attempt to deconstruct the old tradition of girlie calendars.

Williams’ Instagram feed is often full of selfies and posed images where she displays her body in a manner and extent of her choosing. Her Instagram feed definitely shows the same third-wave ownership of her own body as the SI cover. Instagram being the internet, you do want to avoid reading the comments.

Williams’ Instagram feed is often full of selfies and posed images where she displays her body in a manner and extent of her choosing. Her Instagram feed definitely shows the same third-wave ownership of her own body as the SI cover. Instagram being the internet, you do want to avoid reading the comments.

It’s not just instagram comments where Williams gets pushback from this third-wave ideal. There was controversy when her Sportswoman of the Year issue hit the stands. For instance, Rick Morrissey of the Chicago Sun-Times just wasn’t having it. “The magazine put her on its cover looking like she wants one thing, and it’s not a chat with the line judge,” he says. “…. You can argue that the only thing that matters is what Williams thinks of the photo. But that would be pretending an ogling audience isn’t there, and that’s ridiculous. Sex is in the eye of the beholder, and many of the beholders of Sports Illustrated happen to be men. If some of them are thinking, ‘Now there’s a powerful woman!’ many more are thinking, ‘If you tied me up, Serena, I wouldn’t complain.'” Note that Morrisey’s reaction centers on the response of men, the only demographic that matters.

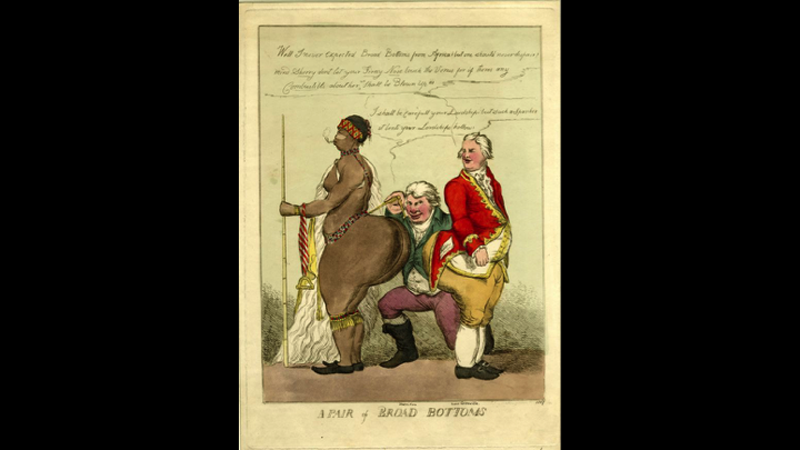

The intersection of sports, sex, race, and body image is a tangled one. James McKay and Helen Johnson argue that both Williams sisters are often described in a manner they describe as “pornographic eroticism,” arguing that “the racialized anxieties that drive censorious responses to African American sportswomen are most effectively understood when situated within the historical context of black women’s enslavement, colonial conquest, and exhibition as ethnographic ‘grotesquerie’. The categorization of black women’s bodies as hyper-muscular and their targeting for lascivious comment mirrors the public and pseudo-scientific response to nineteenth century exhibits of Saartjie Baartman, the South African woman labelled the ‘Hottentot Venus.’” It doesn’t take much thought to see that Morrissey’s column slots into this framework quite neatly. In the face of this, I agree with something McKay and Johnson say a bit later:

Paying attention to the multifaceted discourses and symbolic expressions through which African American people construct new forms of social identities has contributed to sociological understandings of marginalized people’s responses to racism. Listening to the positive responses of African American women to negative readings of their corporeality could enable the sports industry to cultivate … a ‘black feminist aesthetic that recognizes the black female body as beautiful and desirable’ in its distinction from stereotypes of white beauty.

In that segment, Mckay and Johnson anticipated exactly what Serena Williams was up to with her Sportwoman of the Year cover photo. The most empowering use of photography is its employment to to establish one’s identity; that is 100% what Serena Williams is doing with the throne cover. After two decades in the public eye, during which she was widely photographed and subjected to noxious commentary because of her ethnicity and gender, Williams is, with pictures, staking out a claim as to exactly how she wants to be perceived, exercising a great level of control over the display of her body in photography. She is working in the space of third-wave feminism, which I would argue is largely about agency, which is in turn a central concern of pretty much every contemporary movement towards human dignity.

Or, to step out of the academy and into popular sportswriting, consider this response to that Morrisey column from the sportswriter Kevin Draper:

The irony is that since her ascendance years ago Serena has been criticized by stupid sportswriters for being too muscular, for looking “manly,” and for having an “oozing pumpkin” butt. Now, after being recognized for one of the greatest seasons in the history of tennis, the commanding pose she chooses to strike to express her dominance is deemed … too sexy. Serena Williams has no obligation to anybody other than herself; she likes the cover, and that’s one of two things that matters here. The other is that she’s not just projecting her idea of what a powerful black woman looks like, she in fact is one. You can be sure of few things more than you can be that she does not give a fuck what Rick Morrissey thinks.

If third-wave feminism means anything, it’s the right not to care about the quibbles of a middle-aged white man with a newspaper column.