For the Record is an ongoing (I hope) series where I write a bit about albums that I have strong feelings about, good or bad.

Bluegrass is a weirdly bifurcated world. There’s a joy to the music; even when the lyrics are about heartbreak, misfortune, or murder, it’s impossible to feel too bad when you’re hearing fast picking and high harmonies. But there’s also a joylessness to the milieu out of which the music comes; no area of country music (or, indeed, of music in general, in my personal experience) is as hidebound and hung up on following the rules and doing it the way it’s always been done as bluegrass is. I know from direct experience that musicians-looking-for-musicians listings involving bluegrass will be the most prescriptive out there, and that to even think about getting into a bluegrass band is to run a serious risk of spending half your time bogged down in arguments about the right way to play bluegrass.

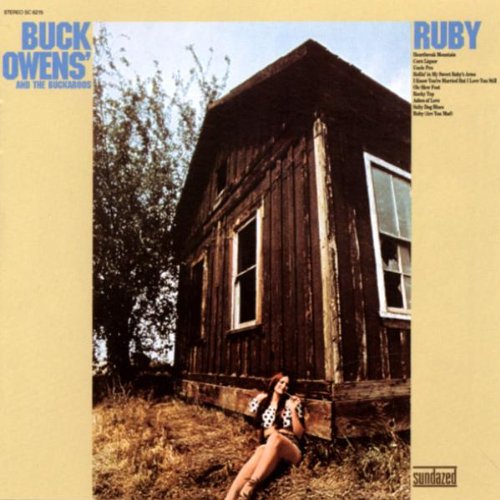

Which is part of why Buck Owens’ Ruby & Other Bluegrass Specials is such a goddamned miracle. It’s an experimental, bordering on trippy, take on bluegrass that actually does take the music to strange new places.

It seems like Buck Owens was tough to love as a human being (if Cocaine and Rhinestones’ Tyler Mahan Coe will just flatly state that a guy was an asshole, he’s a pretty big asshole), but he’s easy to love musically. Owens played an uptempo, electric, driving style of country that paired an absolutely stellar backing band with a willingness to try just about anything. If Owens is considered one of the giants of country music, big chunks of his catalog sound as much like rock as country; his biggest hit, “Act Naturally,” wound up being covered by the Beatles, and he often included early rock numbers like “Johnny B. Goode” in his own sets. The musical gap between Buck Owens and His Buckaroos and revered country-rock pioneers the Flying Burrito Brothers is a very narrow one that mostly comes down to more rigorous standards for musicianship on the Buckaroos’ side.

So think about it: Buck Owens, leading an astonishingly tight, adventurous band that stand juuuuuuust on the country-rock line, decides to make a bluegrass album in 1971. But not a typical reverent, barebones bluegrass album; instead, throwing the usual high-energy nearly-rock band at it with an additional license to get weird in the studio. The result (which is largely old bluegrass standards) isn’t entirely void of traditional bluegrass elements: there are banjos and fiddles on some songs, coexisting with drums and (I think) electric bass; and if one of the cornerstones of bluegrass is high vocal harmonies, there’s a lot of that here, albeit sometimes in weird forms that we’ll get into.

But even in the songs whose arrangements are more straightforward, the whole thing is artificially drenched in reverb in a way that makes everything sound trippy and experimental. It’s the kind of thing that would make a traditionalist’s blood boil, but if you’re not hung up on How Bluegrass Ought to Be, it sounds fantastic. The album’s final song, the obscurely lewd “Salty Dog,” includes a piano part so weirdly reverbed that it sounds like something you’re hearing while having the weirdest goddamned dream you’ve ever had.

And on a few songs Owens and the Buckaroos really let their freak flags fly. “I Know You’re Married But I Love You Still” is one of the weirdest, greatest country music songs I know. The song seems like a typical, unremarkable country song (maybe one that’s a little slow for a “bluegrass” album) until it gets to the chorus, where the old bluegrass trope of high vocal harmonies gets turned on its head. Buckaroo (and frequent Owens harmonizer) Don Rich doubles Owens’ vocals in the chorus singing in a weird falsetto, harmonizing on intervals that I simply haven’t heard anywhere else. Drench the whole thing in reverb again, and you get this weird, great artifact that’s just like nothing else out there. Rich’s harmonies stay weird for next few songs, too, if never quite as prominently as on “You Know I Love You.”

I don’t want to oversell the weirdness of Ruby; it’s not like a Flaming Lips bluegrass album or anything like that. I’m not even sure if an electric guitar appears anywhere on it (although again, I’m pretty sure there’s some electric bass). But it’s still looser, shaggier, less reverent, and just more fun than any other bluegrass album I know of. Asshole or not, Owens and Rich and the rest of the Buckaroos sound like they’re having a blast; and the music feels like it’s been taken out of the display case (where it usually sits inertly on display) and taken out for a spin, consequences be damned. There isn’t a bad song on the album, nor one that isn’t a hell of a lot of fun to listen to. If you’re in a bad mood, put this record on and I promise you’ll feel at least 5% better by the time you get to the end of “Corn Liquor.”