This was originally written as a paper for an art history class in curation.

This was originally written as a paper for an art history class in curation.

Last year, my birthday fell shortly before David Bowie Is, the “first retrospective of the extraordinary career of David Bowie,” closed its run at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago. My wife surprised me with tickets to the long-sold-out show. We packed for a crash road trip, hopped into the car, and drove from Minneapolis to Chicago, listening our way with mounting excitement through the entire Bowie oeuvre during the 10-hour trip.

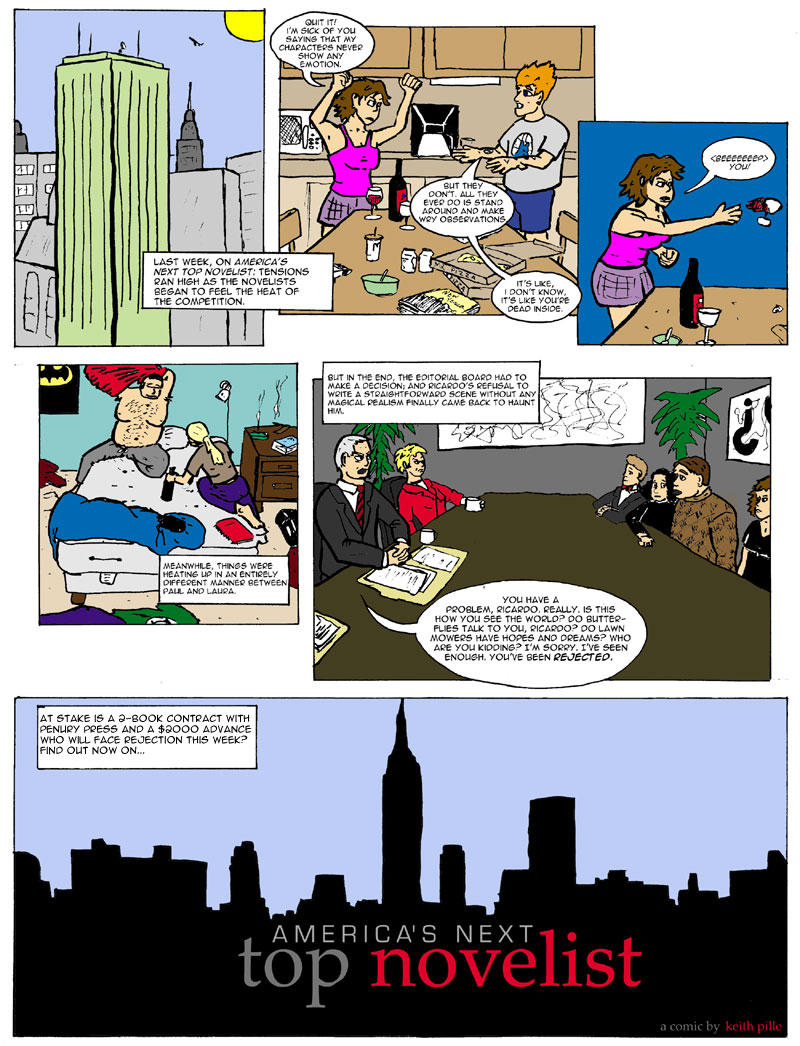

Viewing the exhibit was an overwhelming rush; the line to enter the museum had stretched around the block. The show was designed to hit attendees through multiple senses – as one walked through the space looking at objects, a location-sensitive headset would blast music or interview clips related to the object under view. The crowd itself – packed into the galleries as tightly as the fire marshals would allow – provided a constant buzz of energy as several rooms full of Bowie superfans communed with artifacts connected with the great man.

We left the exhibit exhausted and happily dazed. But on the drive back to Minneapolis, questions started to bubble up as we talked it over. What had we learned in that exhibit? It didn’t really seem like we’d gotten much in the way of new information. The experience had been intense and fun, but had there been an intellectual point? Had the whole thing really been an enjoyable but ultimately empty wallow in pop idolatry? As months passed and the undigested bolus of David Bowie Is lingered in my head, a slow, slinking surety settled in that it had all been a lot of sound and fury, signifying nothing.